What I Learned from

6 Incarcerated Teen Girls

I walk the yard at L.A.’s Central Juvenile Hall. On my way to the classroom where I teach, I pick up writing paper, a roster and snacks (Flamin’ Hot Cheetos are a favorite). The gleaming towers of USC’s medical school and hospital are visible just beyond the compound’s fences. I’m always struck by the contrast of opportunity and care that vista represents.

they've committed crimes—some stupid, some serious . . .

I pass through multiple gates, which open with a loud snap and then bang metallically shut. These sounds define juvie. Boys and girls cross the yard in orderly lines and under guard. I’ve been teaching awhile, so I’ll get a shout out from a student or two:

"Shelley d!"

I say “Yo” back to my girls, these bright, joyfully unruly, funny, potty-mouthed 14-to-18-year-olds. Some are mothers. They’ve committed crimes—some stupid, some serious—but now they show up for class to write, and most importantly, to be listened to.

For more than a year, I’ve been a teacher for InsideOUT Writers, a nonprofit that uses creative writing to empower youth and reduce recidivism. My purpose is to guide my teens to a written expression of feeling, imagination and life experience. I ask them to read their writing out loud to me and their peers so they can not only be heard but also respected for what they have to say.

My classroom reverberates with finger snaps and applause.

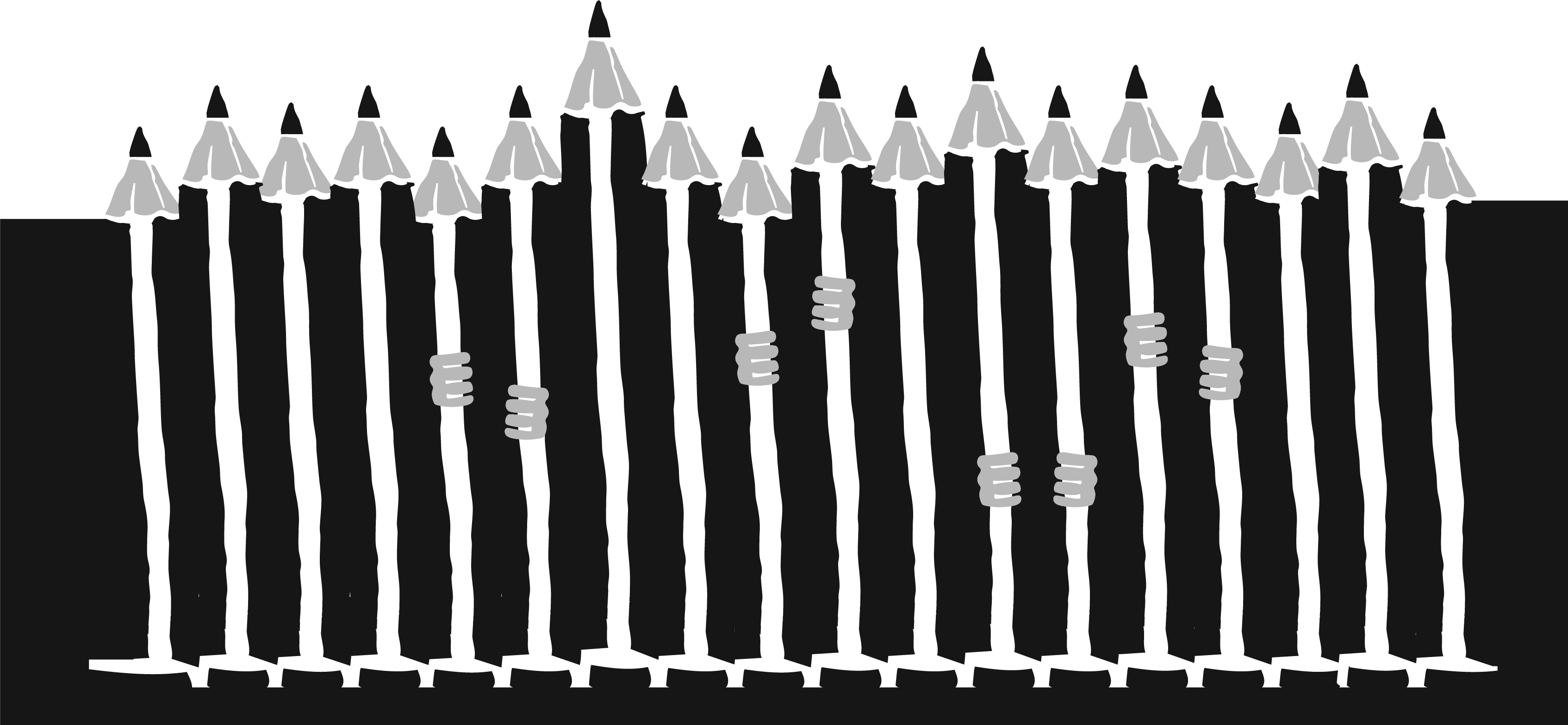

Pens are treated as weapons, carefully distributed and collected, but I never feel unsafe.

I enter my unit and set up the desks. I never know exactly how many girls will show. The roster tells me one thing, but if you’ve been fighting or were written up, you’re barred from class. Today, I’ve got a party of six. Once my group sits, I can hand them pens. Pens are treated as weapons, carefully distributed and collected, but I never feel unsafe. There’s a guard in the room with me who can be motherly or tough, depending on the behavior and the mood in the room.

Today’s lesson is meant to take the girls away—to expose them to a new environment and have them imagine being there. I’d fallen in love with the great outdoors when I was 12, on a family kayaking trip to Maine, and I can still conjure up the sounds and softness of tall grasses in the breeze, water lapping. Now I want to share this experience with my girls. To create the lesson plan, I’d spent a week as an artist in residence for the Angeles National Forest. Each day I snapped pics of mountain vistas, dusty lizards and ponderosa pines. Upon descending the San Gabriel Mountains, I’d deliver these photos to the grim halls of juvie, where we would meditate on what it’s like out in the wilderness.

Class begins as I pass around the iPad of photos. “Girls, take your time to look at these pictures. These mountains are about an hour away. How do you feel about these pictures? Does this landscape inspire you? Imagine being there. Explore. Fly outside the walls! Write!”

Silence. They hold their pens aloft, expressions neutral. Cute lizards, splendid vistas—Mother Nature holds no sway here. Soon a verbal chorus erupts. “What the hell am I doing up there?” one student asks. “Snakes? Thirst?”

“This is not gonna happen,” another girl replies.

Trauma shadows these girls’ lives, and gaining their trust is difficult. Trust isn’t part of your nature when your mom doesn’t show up for a visit, or won’t pick up when you call. When you take your baby to a park you think is safe only to have bullets start flying.

Clearly I’ve got to pivot, and my own imagination needs a booster shot now. How am I going to make this more interesting for them?

“OK, you’re stuck on a mountain top and you have to get down,” I say instead. “What are you going to do?” My dubious flock grants the pictures one more look. I sit and watch them start to write. When they’re done, they take turns reading, and I realize with relief that the lesson has landed. In fact, they’ve written with as much depth, thought and humor as I could have asked for.

One 17-year-old lays it down like the slam poet she is: “Stuck on a mountain, I’m trynna get down. . . . The whole scenario reminds me of where I am now-stuck on a trip with no way out. . . . Is this my mountain forever or will I find my way down?”

Mountain Tops

Stuck on a mountain, I’m trynna get down. I’ve been here before but not really forest bound. The whole scenario reminds me where I am now–stuck on a trip with no way out.

It’s snakes all around me, they rattle all day; no physical freedom, only my mind gets away. A struggle to survive, trynna live for today. Will I stay on the trail, or again will I stray?

The road remains bumpy, trees confuse my route . . . now I’m going in circles battling with doubts.

Is this mountain my forever or will I find my way down?

A 16-year-old mother is reflective. “When I see your pictures it makes me wanna go and spend time with my son, take a run with my boy. Go and walk and look at the beautiful trees . . . This place makes me relax.”

If I Was In the Woods

When I see your pictures it makes me wanna go and spend time with my son, take a run with my boy.

Go and walk and look at the beautiful trees, the views and other things.

And I would sit down and smoke and just enjoy the day and . . .

This place makes me relax.

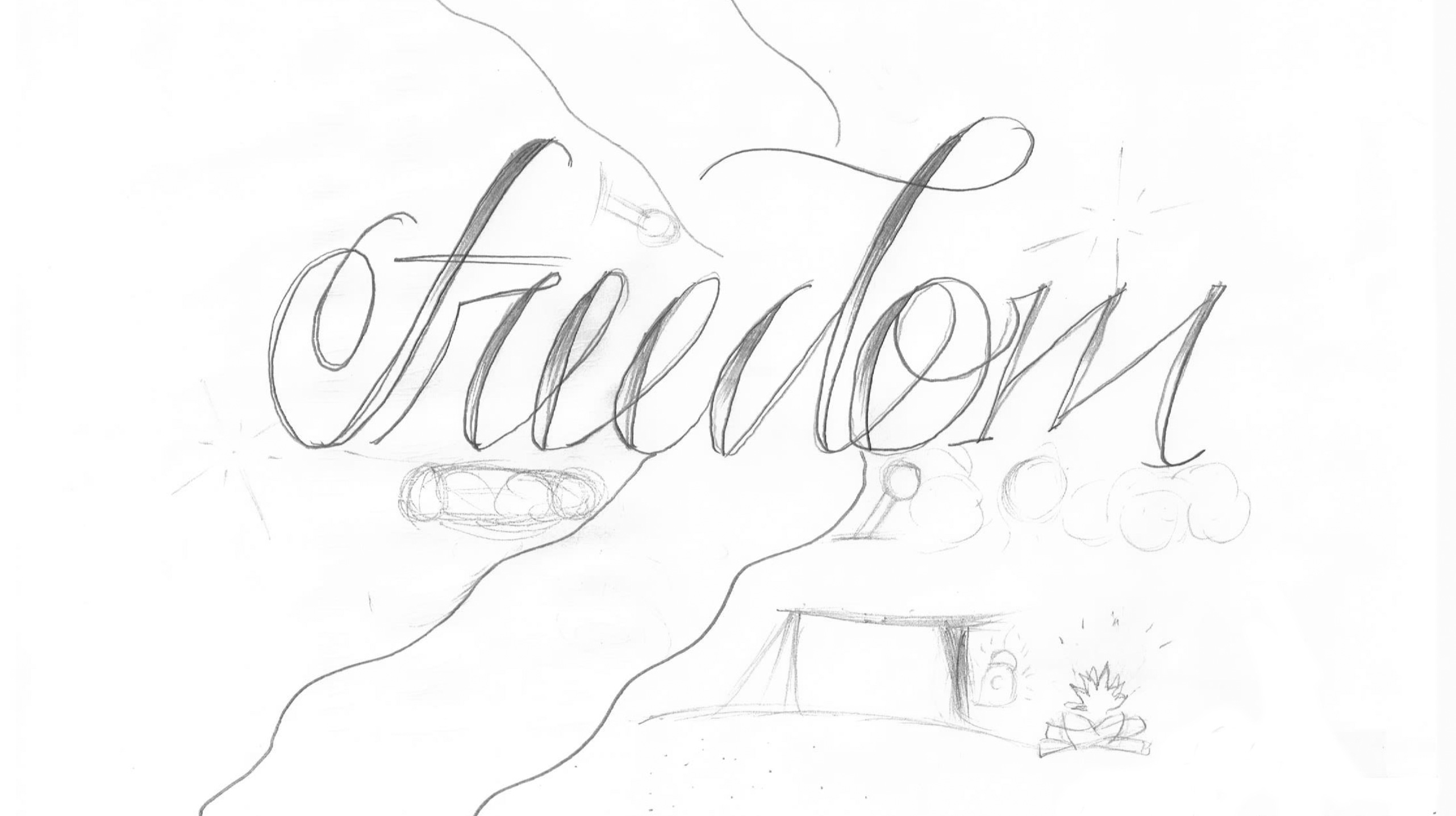

One writer has drawn a wide road leading to shelter and safety. “I want to feel the trail road,” she reads. “I want to see the animals searching for more . . . and shout out any worries that come my way.” She names her piece “Freedom.”

FREEDOM

Mountains feel like home

I want to roam around and explore

I want to feel the trail road

I want to see the animals searching for more

I want to smell the living nature all around me

I want to feel the tree bark under my finger tips

I just want to be in the open

And shout out any worries that come my way

Thoughts on the Wilderness

I’m not walking 2,000 miles–that’s out! (PCT length)

If I had to imagine being in the forest, I would cry and pray to God that a snake doesn’t bite.

If I was on a mountain stranded, I would try to find my way to a road and get a ride. I’ll just walk down.

I would eat some snakes and drink my spit!

Remember

I still remember the look on your face, the wind blowing smoothly on your honey scented hair.

By the way, do you remember when I carved our name on the sugar pine tree? To be honest, I never thought that would be our last trip together.

I still have the famous lizard you wouldn’t stop taking pictures of. I never imagined that little guy would mean the world to me like it does.

Remember all the people you interviewed as we explored and took pictures on the Pacific Crest Trail.